When Doctors Fought for Cannabis: The Forgotten History of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937

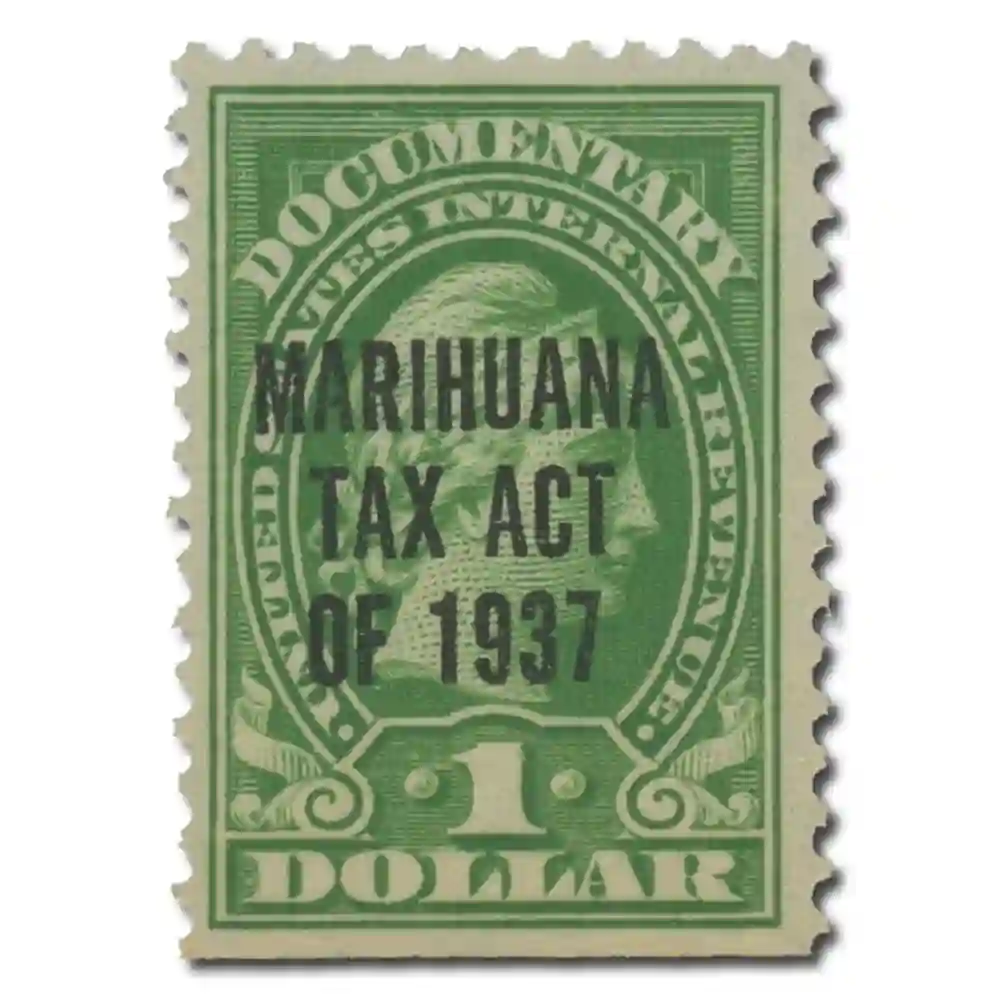

Mention the year 1937 to most cannabis enthusiasts, and they’ll likely recognize it as the year the plant was effectively outlawed in the United States. The Marihuana Tax Act, signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, imposed exorbitant taxes on the cultivation, sale, and possession of cannabis, effectively making it illegal. The popular narrative surrounding this pivotal moment often suggests a broad public health consensus, a necessary step to curb a dangerous drug.

Yet, lurking in the dusty annals of history is a truly obscure, yet profoundly significant, fact: a powerful medical organization, the American Medical Association (AMA), vehemently opposed the Marihuana Tax Act. Far from supporting prohibition, the nation’s leading doctors argued passionately that cannabis was a valuable medicine, and outlawing it would be a grave mistake. This forgotten chapter reveals a stark tension between medical knowledge and political will, a tension that echoes through today’s debates.

Prior to 1937, cannabis was a common and legally recognized medicine in the United States. For decades, it had been a staple in American pharmacopoeias, prescribed by doctors in various forms, most notably as tinctures. Physicians used it to treat a wide array of ailments, from insomnia, pain, and migraines to childbirth complications, muscle spasms, and even asthma. It was openly sold in pharmacies and widely accepted as a legitimate therapeutic agent, often under its botanical name, Cannabis sativa.

The push for prohibition was largely spearheaded by Harry Anslinger, the first commissioner of the newly formed Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN). Anslinger, a zealous prohibitionist, launched a relentless campaign to demonize cannabis, using sensationalist propaganda and racially charged rhetoric. He painted a terrifying picture of “marihuana” (a term he popularized to give the plant an exotic, menacing, and foreign connotation, deliberately separating it from its medical identity as cannabis) as a drug that incited violence, insanity, and moral decay, particularly among minority populations. Films like Reefer Madness were a symptom of this fear-mongering campaign.

Against this backdrop of hysteria, the Marihuana Tax Act was drafted. Crucially, it was done without any consultation with the medical community. When the bill came before Congress, the AMA, through its legislative counsel, Dr. William C. Woodward, mounted a surprising and strong opposition.

Dr. Woodward’s testimony before the House Ways and Means Committee on May 4, 1937, was a masterclass in scientific reasoning against political expediency. He expressed the AMA’s profound indignation and bewilderment that a bill concerning a substance widely used in medicine was being considered without any input from medical experts. He stated emphatically:

“We are not in favor of the Marihuana Tax Act. We have no evidence that marihuana is a dangerous drug… We are not convinced that it is a serious problem.”

Woodward went on to meticulously dismantle the FBN’s claims. He highlighted that the medical literature contained no evidence of widespread addiction, violence, or insanity attributed to cannabis use. He pointed out that the AMA and its members had never been consulted on the alleged public health crisis. Furthermore, he criticized the use of the foreign term “marihuana,” arguing that it obscured the fact that the bill was targeting Cannabis sativa, a plant familiar to every physician. Doctors, he argued, would be forced to abandon a useful medicine simply because the government arbitrarily changed its name and imposed prohibitive regulations.

The AMA’s primary concerns were clear:

- Lack of Medical Justification: There was no scientific basis for classifying cannabis as a dangerous narcotic deserving of prohibition.

- Hindrance to Medical Practice: The Act would severely restrict physicians’ ability to prescribe a valuable therapeutic agent and impede essential medical research.

- Procedural Overreach: The government was legislating on medical matters without consulting the scientific or medical community.

- Linguistic Deception: The deliberate use of “marihuana” was a tactic to mislead the public and lawmakers about the true nature of the plant being targeted.

Despite the AMA’s compelling and rational arguments, their pleas were largely ignored. The political will, fueled by Anslinger’s propaganda and a desire to consolidate power, proved overwhelming. The Marihuana Tax Act was passed, ushering in decades of prohibition that would profoundly alter the relationship between Americans and cannabis. Physicians quickly removed cannabis from their formularies, research was halted, and the plant’s medical utility was systematically erased from public consciousness.

This forgotten chapter in cannabis history serves as a powerful reminder. It underscores that the prohibition of cannabis was not a consequence of scientific consensus or overwhelming medical evidence, but rather a product of calculated political maneuvering, social prejudice, and fear-mongering. Dr. Woodward and the AMA stood as a beacon of reason, advocating for patients and scientific integrity. Their forgotten struggle sheds light on the arbitrary foundations of cannabis prohibition and lends historical weight to the ongoing efforts to restore cannabis to its rightful place as a recognized medicine and a plant deserving of respect and scientific inquiry.